Breast Cancer Facts in a Sea Of Pink

I am so thrilled that my sorority sister Shannon Tierney agreed to write a HerKentucky guest post about breast cancer awareness month, "pinkwashing", and the facts that every woman needs to know.

I've known Shannon since our undergrad days when she was our Phi Mu pledge class president. These days, she's a Seattle-based breast oncology surgeon, a mother of two, and an active patron of the arts. Shannon is an Ashland, KY native who holds a B.S. from Transylvania University, an M.S. from the University of Virginia, and an M.D. from Washington University in St. Louis. -- HCW

In recent years, the colors of October seem to have changed from red, orange, and gold to pink, pink and more pink. I have always loved pink, well before becoming a breast cancer surgeon, even before my Phi Mu days in college, but like many of us, I find the pink of October overwhelming, especially at this point in the month. I appreciate and endorse the continued focus on breast cancer, but often the true issues, the important information, get drowned out by the rah-rah-rah of the awareness campaigns. Many women (and men) are “aware” of breast cancer, but never truly become aware of what it really is, what it really means, until they find themselves dealing with the cold terror of a palpable mass or a call-back after mammogram.

They need information, not just pink blenders.(Click to tweet!)

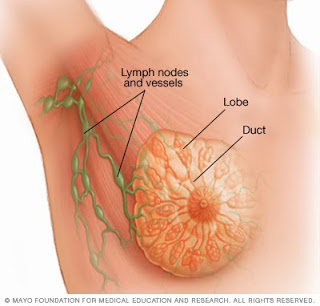

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in the US, affecting 1 in 8 women in their lifetime. Breast cancer usually involves cells that line the milk ducts or lobules which then undergo mutations that escape the body’s usual self-protection mechanism. These cells develop the ability to multiply rapidly, grow, invade, attract blood vessels for nutrients, and set up camp elsewhere in the body.

Due to screening with mammograms, most cancers are caught early. The survival rate from breast cancer has improved substantially, in part due to early detection and in part due to advances in treatment, but it is still the second leading cause of cancer death in women. Cancers can develop that are not seen well on mammograms, or that grow rapidly enough that they are felt in the breast in between mammograms, but these days, most are caught on screening before they are that large. Mammograms are a large source of stress for many women, not to mention uncomfortable, though we haven’t yet developed a better technology to replace them. Many women do get called back for additional images, which often are enough to allow the radiologist to see clearly and rule out any abnormalities. Others have to go on to ultrasounds and needle biopsies, but often the radiologist can predict the likelihood of finding anything serious (the BIRADS score.) Anything that is abnormal or cancerous is usually leads to a referral to see a breast surgeon. Abnormal cells often are removed to be sure that’s all they are – that there is nothing more serious in the area adjacent to that. Women with cancer often undergo additional imaging, which may include MRIs, bone scans, or CT scans, to determine the best course of treatment.

About 30% of breast cancers are ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS, which is the non-invasive form of breast cancer. The cancerous cells are (currently) confined to the milk ducts. These cancers are still treated similarly to invasive breast cancers (minus chemotherapy) because at least half will progress to invasive cancer. Someday, hopefully, we will be able to determine which will progress and which won’t, so that we can reduce the amount of treatment that women need. We are already making progress with that, developing tests which may tell us which women with DCIS can safely skip radiation treatment after lumpectomy. The remaining 70% are invasive cancers, which are highly likely to spread if not treated.

Treatments usually involve surgery to remove the cancerous cells in the breast and usually any in the lymph nodes under the arm. For smaller cancers, the woman can choose whether to have a lumpectomy, removal of the tumor only, or a mastectomy, removal of the entire breast. There is no survival advantage to having a mastectomy, though there may be other advantages. It’s largely a personal choice. Surgery may be followed up with radiation for women who have had lumpectomies or who have had mastectomies for extensive cancer. For breast cancers that are sensitive to hormones (a trait they inherit from the normal, healthy breast cells), antiestrogen pills will usually be used, and sometimes can be used alone without chemotherapy. Cancers that are hormone negative usually require chemotherapy, unless they are quite small. There are other “targeted” treatments that are directed towards unusual characteristics of breast cancer cells, which hopefully minimize the damage to other healthy cells.

For some women with small cancers, treatment may be short and relatively easy. Others may have months of treatment, or several reconstructive surgeries. However, the earlier that breast cancer is caught, the more options are available for treatment. I understand the fear and denial that may take over when the discussion turns from pink ribbons to the reality of breast cancer, but that tends only to prolong the worry and limit the options. So, if the overwhelming pinkness of October encourages someone to go ahead and get that first mammogram, or to check out that lump that is probably nothing, then bring on the pink.